No effective treatment for Alzheimer's is yet in sight, but better diagnostics, deeper scientific understanding and an encouraging drug trial are all leading to a positive mood, as the largest Alzheimer’s research conference of the year begins Sunday in Chicago, USA Today reports.

“There have been plenty of disappointments and sadly I’m an expert in those disappointments,” said Stephen Salloway, director of the Memory and Aging Program at Butler Hospital in Rhode Island and a professor of neurology at the Alpert Medical School of Brown University. “ (But) I’m quite bullish and think we’re making significant progress.”

Much of the recent optimism surrounds a drug trial that will report out more details at the Alzheimer's Association International Conference.

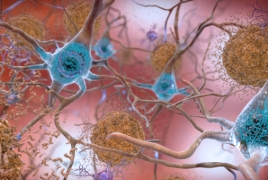

In that small trial, a drug seems to have removed a protein called amyloid, which is the hallmark of Alzheimer’s. All previous trials attacking amyloid, including some costing hundreds of millions of dollars, have failed in patients. The new study suggests it’s because they were given too little, too late.

“You’re going to have to move early and be very aggressive,” said Reisa Sperling, who directs the Center for Alzheimer Research and Treatment at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

Eighteen months after they began taking the experimental drug – called BAN2401 –patients who received the highest dose saw a dramatic drop in the amyloid in their brains as well as signs that disease progression had slowed, according to Biogen, which is developing the drug along with Japanese company Essai. Detailed results and more recent findings are expected to be presented at the conference.

“I’ve seen the data and I find them very encouraging for a change,” said Sperling, a professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School.

Exactly how early the treatments should be started remains unclear.

Other trials, including the recently announced Alzheimer’s Prevention Initiative Generation Program, a collaboration between drug companies Novartis and Amgen and the nonprofit Banner Alzheimer’s Institute, are trying similar drugs earlier in the disease, before people have noticeable symptoms.

Such early approaches are largely possible because of a diagnostic test approved in 2012 that can confirm amyloid in the brain before the person suffers obvious memory loss. The PET scan diagnostic is not available to most patients, because it’s not routinely covered by Medicare, but has been used in clinical trials to make sure that only people who have amyloid in their brains are given the anti-amyloid drugs. Many earlier anti-amyloid drug trials turned out to have included people who had dementia, but not Alzheimer’s, so the drug would never have worked on them.

About 5.7 million Americans have Alzheimer’s disease, which is the most common form of dementia. That number is expected to climb to nearly 14 million by 2050, as the population ages.

Although anti-amyloid drugs are still considered the most promising to treat early forms of Alzheimer’s, researchers are also developing candidate drugs that act on other aspects of the disease. An experimental diagnostic PET scan can visualize the build-up of another protein that’s characteristic of Alzheimer’s, called tau.

Trials are underway to see if drugs that remove tau will benefit people with Alzheimer’s. Sperling said she’s excited about the potential of this work, but notes that researchers must still figure out how much of these drugs to give, which form of tau to go after, and what stage of the disease to treat with these drugs. “We have years of work ahead,” she said.