For the most part, the photos were taken by Russian soldiers and journalists, as well as German military and officials, who were in the Ottoman Empire during the World War I.

PanARMENIAN.Net presents 11 photos, which tell the historical truth.

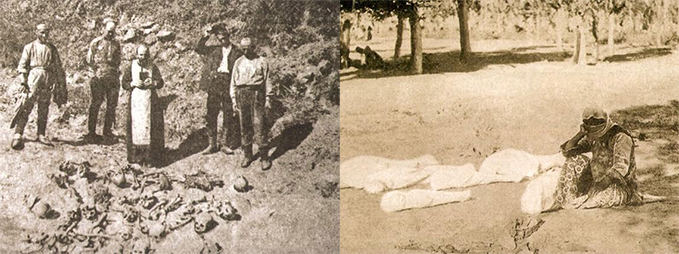

Photos 1 and 2. The photograph on the left shows the bodies of Trabzon Armenians and a priest who accompanied the Russian army during the military campaign. A Russian officer stands behind the clergyman offering a prayer for the killed Armenians. The other three people are civilians, probably local residents.

After Turks suffered defeat in Sarikamis, the Russian army managed to take control over a number of areas in Western Armenia. Russian soldiers witnessed horrible scenes, saw piles of corpses, skulls and skeletons throughout the territory, especially in Armenian-populated towns and villages, their surroundings, under bridges and along the roads. Those were bodies of hacked, shot or burnt Armenians. During the breaks between battles, Russian troops and Armenian volunteers tried to bury as many martyrs as possible.

The great number of dead bodies ruled out any possibility of swimming near Trabzon shores in summer 1915.

“I saw tears, sorrow, curses, murders and suicides, people burnt alive, dying from fear, fires, shots and persecutions. I saw hundreds of corpses every day. Young women and children were taken away from Christian families and schools, entrusted to Muslim families and forcibly Islamized. Many were kidnapped and thrown into the Black Sea or Degirmen River. These are my last, indelible memories from Trabzon that torture and trouble my soul and almost deranged me,” Italian consul to Trabzon Giacomo Gorrini wrote in August 1915.

The photograph on the right shows a woman from Van, who lost all of her family members but managed to reach a forest near Etchmiadzin. The dead bodies were wrapped in white sheets in an attempt to prevent typhus outbreak. The photo was named “Despair”: a mother surrounded by the corpses of her five children in white sheets, one of the most typical scenes of the Armenian Genocide.

In 1915, dozens of thousands of Armenian residents of Van and nearby villages, who survived the slaughter, were sent to Eastern Armenia together with retreating Russian soldiers. During their way, the convoy of refugees was numerously attacked by Kurdish tribes. Upon reaching the Erivan governorate of the Russian Empire, most of the Armenian refugees settled in Etchmiadzin and surrounding villages. Later, thousands of them died during malaria and typhus outbreaks.

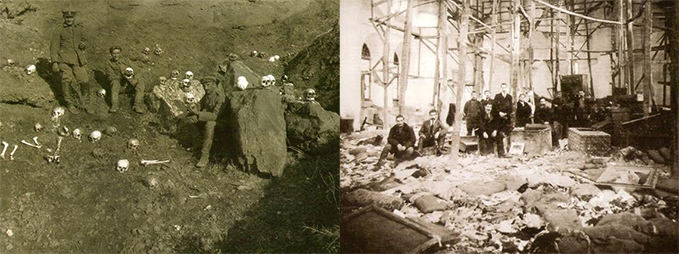

Photos 3 and 4. The photograph on the left shows German soldiers in the Ottoman Empire, who posed near the corpses of Armenians murdered near Hekimhan, Malatya. The photo was dated as November 18, 1918. The Germans gave the negative to Islamized Armenian photographer Tsolak Dildilian, who saved it, thinking that the remains of his relatives killed at that site in mid-1915 could be in this photo. Probably, the German soldiers allowed him to keep the negative, as the war was over and there was no need to keep it secret despite the Turkish censorship law.

The photograph on the right shows the Armenian church of St. Stepanos in Trabzon that was turned into a warehouse. In 1915, a part of Armenian properties was brought to the church and then auctioned by special committees formed by the Turkish government. After the armistice in 1918, a group of Armenians, who returned to Trabzon, took a photo in the church.

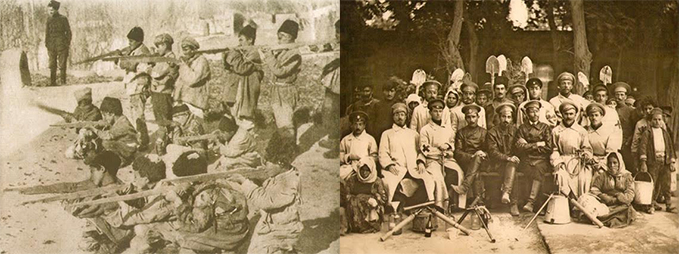

Photos 5 and 6. The photo on the left was published in National Geographic edition in 1919 together with the article by correspondent Maynard Owen Williams. The armed kids in the photo, the oldest of whom was 12 years old, were photographed after the heroic resistance of Van.

“Carrying wooden rifles, they had come to the governor of Van Hambartsumiants to demand real weapons, for they were ready to fight till the end and defend their families, with some of their relatives already gone,” Williams wrote.

During the years of the Armenian Genocide self-defense battles were held in several cities of Western Armenia. The fierce resistance that took place in the city of Van from April 7 to May 6, 1915 ended in a victory. The heroic resistance of Van was the longest and the most decisive one. Residents of Van fought courageously. Women, elderly and children took part in the bloody resistance realizing how important it was to defend their homes and dignity.

The photograph on the right was taken in summer 1915, when insanitary conditions resulted in the outbreak of typhus. Lack of food, water and medical assistance, as well as the baking sun gave a boost to the epidemic. Several armed groups were formed to collect and bury the bodies. The photo shows gravediggers.

In late 1914 and early 1915, about 50,000 Armenians migrated from Western Armenia, Persia and the surrounding regions to the Tiflis and Erivan provinces. The Russian government ordered to form special committees to deal with the refugees. A part of the refugees, who arrived from Van, Bitlis, Mush and Hnus, found shelter in the forest near Etchmiadzin, in the area between the Lake Aygr and Hatunarkh village.

Instead of rendering medical assistance, the local authorities allocated carts that drove round the forest, gathered the corpses and took to bury them. No one knew where the bodies were taken, according to Genocide survivor Sahak Karapetyan.

Photo 7. The photograph shows the skulls and bones of Armenians killed by Turkish soldiers. It was made on the ruins of a house in Aghjan village of Mush province, where hundreds of men, women and children were burnt alive.

During the years of Genocide, Turkish thugs resorted to various methods of killing Armenians. They often closed the windows and doors and threw Armenians through the chimney unless the house was filled. Then they poured kerosene and set the house on fire. Thousands of people were killed this way.

The photograph was made by Frank Danielian, who served in a regiment of Armenian-American volunteers for the Caucasus and had a possibility to take photos in different cities of Western Armenia, depicting the atrocities against Armenians.

A part of the photos taken by Danielian was published in the American press. They were first printed in the edition of Leslie’s Illustrated on June 28, 1917.

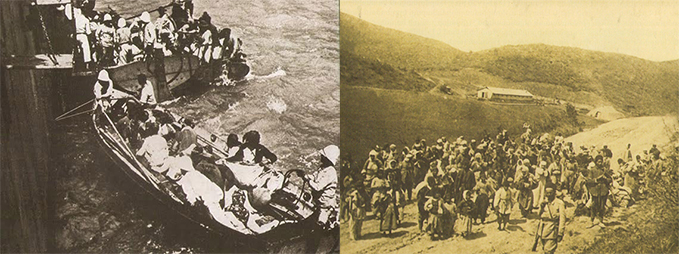

Photos 8 and 9. The photo on the left which shows a scene of evacuation of Armenians of Musaler by French sailors was published in The Sphere newspaper.

In spring 1915, Turkish authorities began the deportation and extermination of the Armenian population of Western Armenia and other regions of the Ottoman Empire. On July 30, Armenian inhabitants of Suedia (also known in English as Seleucia by the Sea, presently located at the seaside village of Çevlik near the town of Samandağ in the Hatay Province of Turkey), ascended the Musaler and organized a resistance. On September 10, 1915, responding to the call for help by the people of Musaler, French warship Jeanne d’Arc began shelling Turkish positions. French admiral Dartige du Fournet ordered around 4000 Armenians to be evacuated by warships to Egypt’s Port Said harbor.

On September 12, five French warships - Guichen, Desaix, Foudre, L’Amiral Charner and D’Estrée approached the shore, anchored and lowered canoes to begin the rescue operation that lasted three days. Women, children and elderly people got aboard first. Men followed. During those hard but victorious days many children were born and were given names symbolizing freedom and rescue. One of the children was named Guichen in honor of the rescue ship.

The photograph on the right belongs to a British army officer, who named it “Forcibly replaced Armenians.” The photo shows a convoy of deported Armenian women and children escorted by armed soldiers. After the issue of deportation order, Armenians were given little time to pack some clothes and foods to hit the road. Struck with panic, many of them sold their properties at a fraction of the cost. The convoy was from time to time ambushed by Turkish and Kurdish gangs. Many of the deportees died on the way from hunger, diseases and violence.

Photos 10 and 11. The photograph on the left shows a burial site of about 270 Armenian refugees from the village of Lalband (presently Shirakamut) not far from Kiraklisa (Vanadzor). On July 1, 1918, the local Turks murdered the Armenians near Katarinenfeld (now Bolnis). The picture was attached to the report by German lieutenant Volker, who witnessed the crime. The original photo is kept in the archive of the German Foreign Ministry.

The photograph on the right shows Varduhi Petrosyan, a widow with two sons after the slaughter in Mush in the winter of 1915-16. It was presumably taken by Norwegian missionary Bodil Biorn, who worked as a nurse in different cities of Western Armenia. In 1915, she witnessed the murders in Mush. Her collection of photographs tells about the everyday life of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire before the Genocide and its consequences. There are also memoirs containing the evidence of the witnesses of the killings, which were conveyed to the Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute by her grandson, Jussi Flemming Biorn.